Isabella Guadagni

This is Isabella Guadagni’s biography, written by her son

Francesco Carloni de Querqui. It was started in the form of weekly

emails to family members and friends during the last months of

Isabella’s life. It continued in the same way after her death. We

have chosen to keep it in the order it was written. Sometimes, other

information not directly pertaining to Isabella’s life, was included

in an email. We have kept it at it was when it was originally

written.

Francesco Carloni de Querqui

Dear Vieri, Carlo, Dino, Sterling, Lucas

As you know my mother did not feel very well last winter so I

rushed to see her in Lecce, Italy, where she lives in my sister

Eleonora and brother-in-law Giandomenico Profilo’s house. Lecce is a

town in Southern Italy, in the center of the heel of the boot, in a

region called Puglia, I think Apulia in English, where Giandomenico

is from and lives. When she saw me and Tony, my oldest son, my

mother smiled and said she wants to live another year. Of which we

were all very happy. Daniel Thuret, the French guy from Roglo, who

is also a distant cousin of ours and who owns a castle, Champroux,

that used to belong to the French Guadagni, heard about my mother’s

bad health, we call her “Nonna” which means “Grandmother” in

Italian, and kindly repeatedly asked me about it. I was touched by

it and decided to send him in several short emails her biography. My

mother Isabella Guadagni is Tony Gaines’ first cousin, 96 years old

and the last surviving of the 18 siblings and Guadagni cousins of

her generation. I thought it might interest you as her experience

was in many ways similar to Antonio’s and to all the Guadagni of her

generation. I will thus copy all of you on the emails I send to

Daniel Thuret about her life. In case you are not interested please

delete them and/or tell me and I will take you off the mailing list.

If Arielle, Kevin and Megan are interested also I will be pleased to

add them to the Guadagni History Family list.

Thank you,

Francesco

Dear Daniel,

Nonna is doing better. When I rushed to see her in February with my

son Pierantonio, she was happy and she told us she wants to live

another year. We are all very happy about it. Let me tell you more

about her, a brief biography, that I might add to my Guadagni book.

As you know she was born on Nov. 15, 1913 in Florence, third

daughter, after Tecla and Beatrice, of Bernardo Guadagni and

Madeleine Querqui. She grew up in Florence. Almost every summer they

went to Le Puybelliard in Vendee'. Grandfather Bernardo, who, like

many Guadagni, me included, was very particular on healthy habits,

took her out of school at the end of the fifth grade because he

thought the air in the classroom with all those children stacked in

one room was not very healthy to breathe. So she was taught by

private teachers but legally she has only a fifth grade elementary

school diploma. As kids, we thought that was very funny. Grandmother

Madeleine always spoke French with her and so did her grandparents

Paul and Jane Querqui and everybody in Vendee' when she went there.

A British governess taught her English and she spoke it with a

strong British accent. My Father, son of Eleanor Graham Allen, an

Anglo-American, teased her gently about it sometimes.

At la Traversa, our mountain house, all the books were in English or

French (La Bibliotheque Rose of Comtesse de Segur). It was hard to

find a book in Italian. At seventeen she was sent one year to Vienna

to learn German, which she spoke fluently all her life. At eighteen

she was sent to Paris, to study in the Art Academy. She loved it

very much, having an artistic talent like many Guadagni, her father

and grandfather, Guadagno, included. I got mine from her. I will

tell you more about her in a following email.

Your cousin and friend,

Francesco

I am going to add a few notes on information Daniel Thuret and my

Italian family know and you do not. Isabella Guadagni’s mother, i.e.

my grandmother, was French, from Vendee, a region of France on the

Atlantic Ocean between Bretagne and Bordeaux. Her name was Madeleine

Querqui and her parents Paul Querqui and Jane Moller. They owned the

castle of Le Puybelliard with a lot of farmland, altogether 1,400

acres, cultivated by peasants, around it. Great-grandma Jane had a

sister, Eliza, widow of my great-grandfather Paul’s brother who

lived in a nearby castle, called Chassenon, also with a lot of

farmland cultivated by peasants. I added the name Querqui to mine

because Jane and Eliza had no brothers or descendants except my

grandmother Madeleine and they were the last of their name.

Francesco

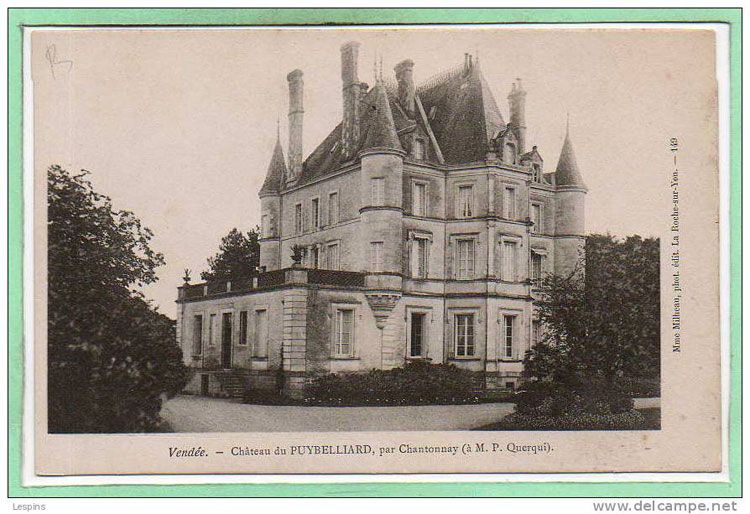

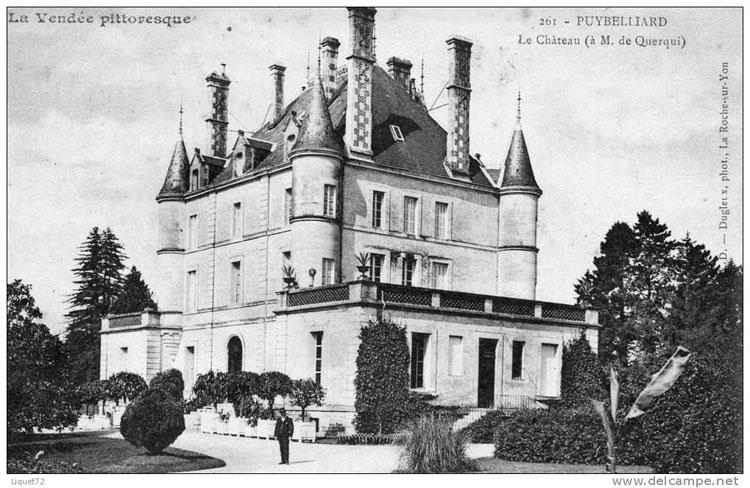

Querqui castle of Le Puybelliard in Vendee’, France. Paul Querqui (1854-1933), Isabella’s French grandfather, can be seen standing in the forefront.

Dear Daniel,

I will continue my mother's biography. I am glad you contacted Edouard and thank you for his regards. Father Vignon died I think one year after I met him in 1994. His book on the Vendetta used to be found in the Musee' Gadagne of Lyon. With Edouard a few years later we visited an old Gadagne castle close to Charly, not the one of Claude de Gadagne though, and as soon as the guide found out I was a Guadagni he gave me 11 copies of the Vendetta free, that he had from the time of the inauguration of the Avenue de Gadagne, and did not know what to do with them. I kept one and distributed the others among family members: in the olden days every Guadagni had a copy of the Passerini, nowadays one of the Vendetta. If I find an extra one it will be my pleasure to send it to you.

Your great-great-grandmother seems a very interesting person. I will go on with the biography. Many Guadagni are interested in it so I forward copies of it to them, among whom is Libuzzi who lives with my mother and can correct any mistakes I made. She just told me that my mother was sent to Vienna, not Zurich to learn German, which makes sense. My mother's two sisters got married, first Beatrice at eighteen with Cosimo Rosselli Del Turco, and then Tecla, the eldest with Francesco Bartolini Baldelli.

After her two older sisters married and left the house, Isabella lived with and took care of her aging parents, Bernardo Guadagni and Madeleine Querqui Guadagni, and her grand-parents, Paul and Jane Querqui who spent more and more time with them. The summer would be at Le Puybelliard in Vendee' or La Traversa in the Tuscan Appennines and the winter in Florence at Villino Guadagni, built by Bernardo next to the Corsini Palace, upon request of his friend Prince Corsini. In 1933 Paul Querqui died and was buried at Le Puybelliard. Jane did not want to live in it alone so she moved in permanently in the villino Guadagni. A few years later, her daughter Madeleine sold the castle of Le Puybelliard. Some land of Le Puybelliard was kept and was later divided among Tecla, Beatrice and Isabella. Now all summer and fall were spent at La Traversa because Bernardo loved woodcock hunting, which is done in the late fall, and winter and spring in Florence. Even though they loved each other tenderly, Bernardo and Madeleine did not share the same bedroom because as a Guadagni Bernardo was an early riser, every morning at 4, he would draw his models of embroidery until 8 and then join Madeleine for breakfast. Then he would go for a walk or hunting till noon. Lunch was at 12:30: always a first course, soup, rice or pasta, an entree with two or three side dishes, then cheese, then dessert and at the end fruit. Then nap from 2 to 4; then tennis, Bernardo had a tennis court built in his back yard, with friends and relatives until 7 pm. In spite of her stiff leg Madeleine could play tennis also. Then dinner at 7:30, playing cards after dinner and to bed at 9. Madeleine stayed up later reading. Isabella would go for long walks up the mountains, read mostly mystery novels in French or English or historical novels, drew and painted calendars for charity, participated as a nurse helper in the pilgimages of the sick to Lourdes and Loreto. Half a mile steep up the Cucuzzolo mountain next to La Traversa amid thick woods of pine and fir trees was La Capannella, the mountain house of Bernardo's eldest brother, Guitto, who would come there every summer with his wife, Dorothy Schlesinger, who was British, and his 4 sons, Guadagno, Migliore, Vieri and Donato. A marriage was almost arranged between Guitto and the daughter of the last Duke de Gadagne, in France, to reunite the two branches of the Family. But eventually the French Gadagne married the marquis de Galard, and Guitto married Dorothy. Uncle Guitto loved trees and he planted scores of acres of trees at Masseto, the Guadagni villa near Florence and La Capannella.

In November 1940 Grandfather Bernardo Guadagni died at La Traversa. He had been shooting woodcocks (beccaccia?) until a few days before he died. Then he had a cold that restarted a dormant tuberculosis he had when he was young and in a few days he passed away. There was a heavy snowstorm up in the mountains, where La Traversa is, and the only road taking to Florence was blocked for many days. Finally Madeleine Querqui Guadagni and Isabella could take Bernardo's body back to Florence. Eventually though he was buried in the little graveyard a few yards down the dirt road that borders the lower gate of La Traversa's garden.

Except for the two-yard wide dirt road, La Traversa, the graveyard and a narrow bubbling stream, there are only trees and the gentle slope of the mountain. A year later, in Florence, Madeleine died also. She was only 52, while Bernardo had died at 72. I think without her beloved husband she had no more reasons to live. She died of cancer, but not of the lungs, even though she had been a heavy smoker for many years. Isabella never smoked but she always enjoyed smoking people around her because they reminded her of her mother. Jane Moller Querqui lived another year at the Villino Guadagni. Her mind had gone a little and she never realized that Madeleine had passed away. Often in the morning, while she was having breakfast with Isabella she would ask:"Isabelle, ou' est Madeleine? Je ne l'ai pas encore vue ce matin" "Isabella where is Madeleine? I have not seen her yet this morning". Then she died also and was buried in the "Cimitero degli inglesi" "English or Protestant Graveyard" in Piazzale Donatello in Florence. She was Huguenot. Madeleine instead was buried next to her husband in the graveyard of La Traversa. It is a rectangular two yard long gray violet stone with Bernardo and Madeleine Guadagni written on it. When we were children Isabella, our mother, would take us there to pray sometimes.

When the three Guadagni sisters divided the inheritance, uncle Cosimo Rosselli Del Turco, aunt Beatrice's husband, was very nice and insisted that Isabella inherit all of the villino Guadagni plus her share of Le Puybelliard and other goods, because she was the only unmarried and had to fend for herself. Uncle Cosimo acted as the older brother that Isabella always wanted and he was always extremely nice also with us children and everybody including the poor and the downtrodden. A few years before, Bernardo and Madeleine tried to arrange a marriage between a wealthy Florentine nobleman and Isabella. But even though the suitor was a charming young man, Isabella was too international and he too Italian for her and the marriage did not happen.

Now Isabella was left all alone in her thirty room house. It was 1942 and the war was raging in Africa and Russia. Isabella enlisted as a Red Cross and daringly was sent on hospital ships in the Mediterranean and in hospital trains in Greece and Russia. She was with the Duchess of Aosta, cousin of the King of Italy. While all the other Red Cross were full of respect and deference for the Duchess and agreed to whatever she said, as a Guadagni Isabella felt equal to the Duchess and she spoke her mind when she thought the Duchess was wrong. So the Duchess used to nickname her jokingly "sorella brontolona" "grumpy sister". Isabella was awarded many decorations, including from the German Army, but never talked about them and we did not even know they existed. One day, a few years ago, putting in order family archives, I found the document that mentioned them.

I am adding a little parenthesis, addressed to Daniel Thuret. I included Giovanna Rosselli Del Turco Brancoli Busdraghi (aunt Beatrice Guadagni Rosselli Del Turco youngest daughter), born in 1940, in my Guadagni recipient list. I think she will be interested in my mother’s biography. Her husband Piero, now a retired diplomat, is very interested in History and Genealogy. Her three children, Anna Pia, my goddaughter, Benedetto, and Giulia all have the French Baccalaureat, like my brother Bernardo’s children, and like us Carloni. My sister got hers in Vendee’, France, I got mine in Jaffa, Israel, while my father was Conseiller d’Ambassade in Tel Aviv. Bernardo, eventually, got his high school diploma in Italian, by correspondence, when he was in Caracas, Venezuela, where my father was Consul General, but he did all his high school studies until Junior high school included, in French, in Jaffa. Often Italian children of diplomats get their High School diploma in French, because you can find French schools in every country in the world, and so you do not have to change school language, while Italian schools are rare, and the French Baccalaureat allows you to go to Italian Universities as well as an Italian licenza liceale (High School diploma). This has nothing to do with Guadagni History, but I am very proud of how the French culture survives in my family and I wanted to share it with you.

Your cousin and friend,

Francesco

In the spring of 1943 Isabella returned to Florence. The war in Russia was lost and the Italian Army had retreated back to Italy. Isabella did not like to live alone. She enjoyed taking care of other people like she had done in the past ten years with her aging parents and French grand-parents. So she left the Villino Guadagni empty and moved into her sister Beatrice Guadagni Rosselli Del Turco’s house. Beatrice and her husband Cosimo by now had five children: Laura, Francesca, Marcella, Michele and Giovanna. Giovanna, the youngest, was born in 1940. All the others, the eldest being Laura, were born more or less two and a half years apart from each other. They were very happy to get some help. My mother had her own personal maid, Ersilia, a very short woman always smiling and happy, who followed her everywhere. So also Ersilia moved from Villino Guadagni to the Rosselli Del Turco’s house. I am adding this detail for my readers who do not know how was life in Europe sixty years ago.

One day my mother was invited to a tea party in the house of Franca Pecori Giraldi, daughter of Marshall of Italy, World War One hero, Count Guglielmo Pecori Giraldi (1858-1941). I am writing these names for Daniel, because Guglielmo Pecori Giraldi is in Roglo, even though his daughter Franca, who as far as I know never got married, and who later became the Baptism Godmother of my sister Eleonora, and her sister Oretta are not. During World War One Pecori Giraldi commanded the Italian troops, who were then allied with French, English and Americans, in the Alps against the Austrians, allied with the Germans. The Emperor of Austria was Franz Joseph of Hapsburg, in Italian Francesco Giuseppe. In 1916, with a daring attack, the Austrian went through the Italian army and tried to get to the city of Vicenza, in the plain, and encircle all the Italian army and win the war. However when they arrived to the mountain of Pasubio, where Pecori Giraldi’s army was, they were blocked. They just could not defeat them. The Italian then started singing a song that immediately became famous: in Italian:”L’Imperator Francesco, volea andare a Vicenza( Emperor Francesco, wanted to go to Vicenza) Arrivato sul Pasubio, perde’ la coincidenza (when he got to Pasubio, he lost the connection…)”.

Let’s go back to the tea party. Isabella was the last one to arrive. The chairs were put in a half-circle and there was only one empty chair left, at the end of the half circle. Isabella sat there. A tall man with a blond mustache and intense blue eyes, the skin burnt by the African sun, and whom she did not know, was sitting next to her.

At the Pecori Giraldi’s party Isabella and the stranger sitting next to her introduced themselves. His name was Antonio Carloni, nicknamed Tonino. They soon found out they had a lot in common. Both of them had a foreign mother, Madeleine Querqui for Isabella, Eleanor Graham Allen for Tonino, and their upbringing had been influenced by them. As a child, Isabella spent most of her summers in Vendee’, France, and her French grandparents and mother aged and died in her house. Tonino’s mother, an American from Rye, New York, even though she married two Italians, Francesco Carloni first, and Aurelio Becattini after she became a widow, and had four children from the first and three from the second, had always and mostly frequented the numerous Anglo-American community in Florence, and so Tonino grew up in a foreign atmosphere. When World War II started and her parents and grandmother passed away, Isabella immediately volunteered to join the Italian troops in the war zone as a Red Cross. When in 1935, under Mussolini, Italy attacked Ethiopia, to conquer a colonial empire like England and France, Tonino was the first Florentine volunteer to enlist for the African campaign, and eventually spent eight years in Ethiopia and Libya, first as an officer in the army and then as functionary in the Colonial Administration. Both were decorated in the war. We mentioned Isabella’s decorations. Tonino was awarded the silver medal in the battle of Azbi, Ethiopia, where leading a gallant charge at the head of his African colonial troops against the Ethiopians he saved the surrounded Italian army from annihilation.

They met again and soon decided to get engaged. Tonino was worried about their future: Italy and Germany were losing the war, the Italian colonial empire had completely collapsed and Tonino was probably going to lose his job in the Colonial Administration. Isabella however was optimistic as she was going to be all her life and trusted God was going to protect them. They got married in Florence in June 1943, three months after they met for the first time, in the church of Santi Apostoli, in the oldest street of Florence, Borgo Santi Apostoli. Tonino’s younger brother, William Porter Carloni, nicknamed Bubi, a Catholic priest and Air Force military chaplain in Libya and Russia, had just returned from a three month retreat on foot from Stalingrad, Russia, and celebrated their marriage. Food was already scarce because of the war, but Vieri Guadagni, who was renting Palazzo Torrigiani half a block from the church, threw a big party for their wedding and he had plenty of delicious food coming from his farm of Masseto. It was a very nice party. Tonino wore his uniform of officer in the colonial army, Isabella was all in white. “Vous avez gagne’ tous les deux le gros lot” (French for “you both hit the jackpot!”) told them winking an old friend, and when they were leaving, going down the majestic Renaissance stone staircase of the palace, Tonino very tall and tanned, Isabella smiling and beaming under her long white veil, another lady said :”Enfin seuls!” (French for “Finally alone!”). I am impressed by how the Florentine nobility, in spite of France being Italy’s enemy in World War II (and France did not want to, it was Mussolini’s Italy who stupidly wanted to imitate Hitler’s Germany by attacking France) continued to speak French.

Tonino and Isabella went to Venice for their honey moon and then moved to Rome where Tonino was still working in the Department of Colonial Affairs. They rented un apartment in Rome next to the 2,000 years old Roman walls, dating from the Roman Empire, and Porta Pia, built by Michelangelo during the Renaissance. Tonino had many friends in Rome, dating from his stay there as an officer before the Ethiopian war, and they led a happy and tranquil social life in spite of the war restrictions. However the political situation changed quickly. In July 1943 Mussolini was deposed from head of the Italian government and imprisoned, because of the continuous defeats of the Italian army in the war against the Anglo-American Allies, who had already conquered Sicily and were getting ready to march towards Rome. In September 1943 the King of Italy fled to Brindisi, in Southern Italy, already freed by the American army, and declared that Italy was changing sides, i.e. now Italy was allied with the Anglo-Americans and fighting against the Germans. The Germans immediately occupied Northern and Central Italy, including Rome, and freed Mussolini, creating “The Italian Social Republic”, with Mussolini as its head. The newly created republic was Fascist and allied with Germany. The Kingdom of Italy was for the moment limited to the parts of Southern Italy that were under Anglo-American control with the hope of freeing sooner or later the rest of the country from the Nazi-Fascist Regimes It was a sad and bloody civil war that was going to last two years until the end of World War II in May 1945.

All the Italian government officials in the R.S.I. (Republica Sociale Italiana, the Fascist Republic) were asked to choose between joining the new republic or remaining faithful to the King and automatically losing their jobs and sometimes their freedom. Tonino chose to remain faithful to the King and was immediately fired. However the German police never gave him any trouble. Because of his American blood, he was very tall, blue-eyed, blond, with fair Anglo-Saxon complexion and spoke perfect fluent German because as a child he grew up with a German governess in the house who spoke and read only German to the children. That is also why his younger brother William Porter was nicknamed “Bubi” which means “baby” in German. However it was hard to live without a salary and so Tonino and Isabella decided to sell the “Villino Guadagni” in Florence. They sold it for a good price to their friend Count Vannicelli. They decided to invest it in a new apartment that was going to be built in Rome and gave their money to the builder. However the builder was a crook and disappeared with all their money. So Isabella sold some of her stock and thus they survived for a year until Rome was freed by the Allies.

During the German occupation it was hard to find food in Rome, but Tecla Guadagni Bartolini Baldelli who lived in the Castle and farm of Montozzi, in Tuscany, would often send them a chicken or a bag of flour with the help of some nice German officer who was going to Rome. Many of Tonino and Isabella’s friends would then come to their apartment and eat Isabella’s home baked bread. Isabella would often meet her friends in Villa Borghese, a huge park in the center of Rome, similar to Central Park in Manhattan. Some of her friends had little children and they would sit on the benches and chat enjoying Rome’s all year round beautiful weather. One day a German officer approached them. A little worried, the ladies looked at him. The officer looked at the little two years old daughter of one of Isabella’s friends. “I had a daughter of the same age, said the officer slowly,…I have just heard she was killed in the bombing of my city in Germany a few days ago…” He saluted the ladies and slowly walked towards a tree. He disappeared behind it and then the ladies heard a revolver shot. Then they saw his body fall dead on the ground, the smoking pistol still in his hand.

Rome was freed by the Allies in the summer of 1944. Everybody immediately loved the American soldiers, who were so kind and generous and compassionate with everybody. The war went on another year in Northern Italy, during which first La Traversa became the headquarters of the German army, then the headquarters of the U.S. army. A bomb fell on it, going through the roof and the attic, then destroying the room where Bernardo Guadagni had died four years before and the sitting room with stone fireplace underneath it together with part of the stone staircase. Eventually all of it was restored and rebuilt after the end of the war.

In Rome Tonino was appointed liaison officer between the U.S. Army command and the Carabinieri (Italian military police) command. On February 8 1945, Tonino and Isabella’s first son was born, they called him Francesco Adalberto, after his paternal grandfather and godfather. His godparents were count Adalberto Figarolo di Gropello, one of Tonino’s dearest friends, and Maria Gloria Becattini, one of Tonino’s younger sisters. On July 1st 1946, Bernardo was born, named after his maternal grandfather. His godparents were duke Bartolo Lopez y Royo di Taurisana, another dear friend of Tonino’s and Laura Torella di Romagnano. Then on January 14th 1949 Eleonora was born, named after her paternal grandmother. The godparents were her uncle Cosimo Rosselli del Turco and Franca Pecori Giraldi.

In June 1946, after a national referendum, Umberto II, King of Italy, went into exile and the Republic was proclaimed in Italy. Many Italians reproached the Monarchy, mostly King Victor Emmanuel III, Umberto’s father, to have allowed Mussolini and the Fascist Party to take over in Italy, in 1922, instead of trying to stop them with the army. Later Tonino admitted that the departure of the King was one of the three saddest moments of his life. The other two happened over twenty years later and I will mention them then.

As there were no more colonies to administer, the Italian government allowed the colonial functionaries to enter the Foreign Affairs Department, if they passed an admission exam. Tonino became a diplomat and was sent to Tunis as a vice-consul in January 1949. Ersilia, Isabella’s personal maid, had never been abroad and was hesitant about going to Africa, so she remained with Aunt Beatrice Guadagni Rosselli del Turco in Florence. As I am the narrator I will now continue the story in first person.

Tonino went to Africa first, while Isabella remained in Rome until the birth of Eleonora. Our new nanny was Miranda, the sister of Father Desiderio, who was the priest of the little church of La Traversa. We all loved Miranda very much. When Eleonora was born, and Miranda brought her to our room to show her to us, I started crying very disappointed. I was four years old and this was my first little sister and Tonino had showed Bernardo and me pictures of little girls with bows in their hair and pretty blue or pink little dresses, and here was Eleonora a bunch of red crying flesh, bald-headed and wrapped in a bathroom towel…!

We left immediately for Tunis. Miranda carried Eleonora in a big basket. We traveled by ship, and we went through a very violent sea storm between Palermo and Tunis. The three of us children and Miranda shared the same cabin. Our suitcases rolled continuously from one side of the cabin floor to the other, banging against our bunks, every time a big wave hit the ship, which was every few seconds, with a lot of noise. Miranda told us to keep our feet on our bunks lest they be squished by the rolling luggage. It was a bit scary but very exciting, at least for me.

The next morning, of a beautiful bright sunny day, we arrived in Tunis. Father was at the dock in his elegant white suit, waiving joyously with his hat. I expected to see elephants, lions, giraffes and Zulu warriors, as we were landing in Africa, but the only animals were a few dogs and everybody was dressed as the people in Rome.

At that time, in 1949, Tunis was a French colony. There were however many Italian immigrants, Tunis being so close to Italy, and that is why it was an important Italian Consulate General. Tonino and Isabella rented a nice two story house, with a large garden, full of palms and other trees, surrounded by a high stone wall, in the French part of town. Most of the Arabs lived in the Kasbah, the Arab quarter.

We had quite a few servants, I do not remember them all. One was Gina, an Italian cook helper, who was very short, with mustaches and joined eyebrows. One day I was at the kitchen door, I think I wanted to ask Gina something, and she came towards me smiling. She put her hands next to my face maybe to caress me. However she had just finished cutting onions for the spaghetti sauce and her fingers reeked of strong raw onion smell. So I told her:”Gina your hands smell!” and I moved backward fast. Gina had a sad and disappointed look on her face and went back to the oven. For a week Gina was sulky and did not talk to Isabella when she met her. Isabella wondered what was the problem. Finally she asked :”Gina, what is happening? You seem upset about something…!” Gina remained silent for a while, then she said:”Madam, the other day young master Francesco told me that my hands smelled…I had just finished cutting onions for the sauce…I think he is too small to have thought about something like that…He must have heard you complaining about it with the Vice-Consul (Tonino was the Vice-Consul)” Isabella told Gina that she had never mentioned something like that to the Vice-Consul, and that she thought Gina was doing such a good job in the kitchen. Then, she called Francesco and asked him if he had said those words to Gina and Francesco admitted it. So she had Francesco go to Gina and personally apologize for it. It was kind of embarassing for five-years old Francesco to do it but he never discussed his mother’s orders. So he did it and Gina immediately smiled and hugged him and kissed him. However Isabella told her children to avoid close contacts with the servants in the future so something similar would not happen again.

Miranda took care of Eleonora, who was a newborn baby and they slept in the same room. Bernardo and I instead had a governess who was Pauline de Villedieu, a distant cousin of ours and a neighbor from Vendee’, France. Pauline was very nice and we loved her. The three of us slept in the same room, Bernardo and I in little beds on one side, Pauline on the other side of the room. Every night before we would fall asleep she would read us a story. She would ask us what we wanted. We would always pick one of the following books: “Les Vacances” of the Countess of Segur, or “Pinocchio” of Collodi. Both were pretty big books that would last at least one or two weeks to read. At the end of one, we would always pick the other. The interesting thing was that “Les Vacances” was in French and “Pinocchio” was in Italian but we were so perfectly bilingual that we never noticed they were written in different languages. Pauline must have known some Italian because she read “Pinocchio” without problems.

Mother (Isabella) talked to us always and only in French from the moment we were born. We were allowed to answer as we wanted and probably spoke a mixture of Italian and French without realizing it. Father (Tonino) spoke always and only

Italian to us. Being Florentine he spoke perfect Italian and he chose never to use any Florentine dialect expressions or pronunciation, as instead many Florentine, even nobles, do. Thinking about it now, knowing that both my parents spoke fluent German and English, it is curious to think that they never thought about hiring an English Miss or a German Fraulein. If you think we were living in a French speaking country, Tunis, we were going to a French school, my mother spoke to us only in French, why did we need a French demoiselle? I presume Isabella wanted to make sure that we grew up half French. At that time we still owned a farm in Vendee’, and Isabella, who never thought about selling any farmland we had, wanted us to be able to talk with our peasants when we grew older. Father instead, realizing that we were going to spend most of our childhood and youth abroad, wanted to make sure we spoke the purest and best Italian possible.

We attended a French private Catholic school, I think of the “Soeurs Blanches” (White Sisters, called like that because they were all dressed in white). Everything was in French, but once or twice a week an Arab teacher came and taught us how to write and read Arab. After all, even though Tunis was a French colony, it was an Arab country. I was always fascinated by starting the Arab book from the last page and reading or writing from right to left. I did kindergarten, first and second grade in Tunis.

Bernardo Guadagni’s family liked cars. Aunt Tecla Guadagni was the first woman in Florence to get a driver’s licence. Bernardo was one of the first Florentine to own a car. Tonino Carloni instead liked horse-drawn carriages. As a young man he used to work as a bank employee while going to the University. The bank where he was working was located in Palazzo Antinori, in piazza Antinori, at the end of via Tornabuoni, the most elegant street in Florence. The fashionable cafes and bars, the Circolo dell’Unione (The Club of the nobles), and famous stores were in it. Many older gentlemen and ladies, in the 1920s, would stroll along via Tornabuoni in their carriages, saluting one another. Young Tonino, every time he could afford it, would rent a horse-drawn carriage and go to work into it, saluting friends and acquaintances along the way.

In Tunis Tonino rented two two horse-drawn carriages, one to take him to work everyday, the other to take Bernardo and me to school and Isabella shopping. Tonino’s carriage, driven by Mr. Cobo, was drawn by two large and magnificent horses of exactly the same color, chestnut brown. Their mane and their tail were black. They were kept spotlessly clean and shiny. The carriage was also a shiny black, polished every day. Mr. Cobo was dressed all in black, with a white shirt and a black cap. His whip was new and long. He would come every morning with his carriage and wait for Father at the door. Tonino would come out with his hat and his gloves and his cane and sit comfortably in the velvet covered back seat. Mr. Cobo would crack his whip in the cool African morning and the two horses would start trotting ahead.

Mr. Cini was our carriage driver. He was Mr. Cobo’s cousin. His two horses were not the same color: one was a darker brown, the other, called Natalino (“Little Christmas”) was beige with brown and white spots located in no specific order all over his back. They were skinnier than Mr Cobo’s and not as big. We loved them. They were “our” horses. Mr. Cini wore a brown and gray jacket and light gray pants, his hat was checkered, his whip was shorter and a bit bent at the top. He was chubby and always smiling and we loved him. He would allow Bernardo and me to sit next to him in the driver’s seat and teach us how to crack the whip. Bernardo became very good at it. Mr. Cini would take us to school every morning and pick us up in the afternoon and take us home. When we were younger, Pauline would sit with us in the back seat, later we would go alone with Mr. Cini. We were the only children in the school picked up by a two horse drawn carriage but we did not notice it. At least our “picker-up” would not get lost in the crowd.

One of the first things I started drawing as a child was horses. They were part of my everyday life. I continued drawing or sketching horses all my life, often on the top or bottom of my school copybooks or books. Bernardo instead liked playing “horse carriage driver”. He would take two chairs, one flat on the floor, with the long part on top, being the horse’s head, neck and back, the other he would sit on and it would be the carriage. He tied a rope around the top of the first chair and it was the reins, which he would hold in one hand. In the other hand he would hold an old whip, that Mr. Cini gave him, and crack it with resounding noise. He would also say:”Ho…ho” when he wanted to slow down or stop his “horses”. When adults asked him what job he wanted to do as a grown-up, he would always answer:” A carriage driver!” If asked “How are you going to get the money to buy horses and carriage?” he would answer:” First I am going to be a vice-consul, later, after I have saved enough money, I will buy horses and carriage.”

During the summer we would rent a house on the beach in La Marza, an elegant seaside resort on the Tunisian coast. Tonino would join us every week-end and spend the week working in Tunis. Mr. Cicchirillo would drive us to La Marza in his taxi. As a little kid cars fascinated me because we had so few contacts with them. I was usually seasick during the trip and had to lie down in the back seat with my head on somebody’s lap. While we would play in the sand and the shallow water under the careful eye of Pauline and Miranda, Isabella and Tonino would swim away in the deep water and chat for a long time. At La Marza we had our first taste of Tunisian cooking, a plate of couscous that a neighbor brought us. As the family of a diplomat we lived in different countries and continents but we always ate only Italian or French cuisine, it depended if the cook was Italian or French. This work is on Isabella’s life and even if I do not always specify it, everything we did and the way we did it reflects her choices and personality.

Our childhood life in Tunis was different from the life of many children nowadays. Bernardo and I spent our time at home with Pauline, Eleonora with Miranda. We only saw our parents for dinner. Pauline combed our hair and washed our face, hands

and knees (we wore shorts and would often play in the yard on our hands and knees) and take us to the dining room. There was a long table and Pauline and we two boys would sit at one corner of it. Eleonora had her high chair on the same side with Miranda next to her to feed her. There were often guests and Father and Mother were usually not sitting next to us. A butler and a maid served us at the table and we as children were served last. Nobody asked us what we wanted to eat, Pauline would just put in our plate what she thought we needed to eat and cut the meat for us. As I said before, the meal always included a first course, pasta, rice or soup (usually in the evening), an entrée with two or three side dishes and a dessert. Our parents and their guests usually talked among themselves and did not even look at us. Isabella would sometimes quickly glance at what we were eating from her seat. As soon as we had finished eating, we would clean our mouth with Pauline’s help, stand up, walk to our parents’ seat and tell them politely good night. Mother would give us a quick kiss on the forehead and Father a smile, from their chairs. We would also go around the table and politely salute our guests, then, go upstairs to our bedroom with Pauline.

If we were afraid at night, we would never dare to call our mother. I do not even remember her bedroom, I think I have never been there. We would call Pauline but she must not have liked us much to climb in her bed because I do not remember Bernardo or I doing it. Mother would never cuddle us on her lap, also because we never saw her. She would never cook a special cake or meal for us because she never cooked or spent any time in the kitchen. That was the cook and the maids’ job. I heard somebody tell me once: ”Your childhood must have been so sad and lonely”. “No, my childhood was unbelievably sheltered and happy and I do not regret one second of it” was my answer and it is true.

In spite of Pauline and Miranda taking care of us, Isabella did not ignore our upbringing. She did a few things that were far-reaching in our lives and very important.

My parents used to get everyday the most important Italian newspaper,”Il Corriere della Sera”, from Milano (by the way it is on it that appeared the article on the Guadagni archives in Masseto). Once a week the Corriere published a small extra paper that came with it, called “il Corriere dei Piccoli”, the children’s newspaper. For about 5 years from the time I was five to when I was ten, every week there was a page called “History of Italy”(for children) that had five or six beautiful colored drawings on it, with information written underneath them. It started with the foundation of Rome and ended with Italy becoming a Republic in 1946. Isabella could have read it to us and then thrown the newspaper away as you normally do. Instead she used to cut off the historical page and glue it on the pages of a big album. So we soon had this beautifully illustrated history of Italy, growing every week. I think pictures speak better than words, at least for me, maybe because I am an artist. I would look at that album over and over again and thus acquire without effort an illustrated backbone of the History of Italy, which otherwise I would have completely ignored, as I did most of my studying in French schools.

We lost the first page of this History of Italy, which recounted the first four centuries of the history of Rome. Maybe that is why I never cared much to deepen my knowledge of the Seven Kings of Rome or of the first centuries of its Republic. Instead I remember by heart the second page: the Punic Wars. The three wars between Carthago, next to Tunis, and Rome. The first picture shows the impressive fleet of Carthago, which in that period, dominated all of the Western Mediterranean. The second shows the newly made Roman fleet sinking the Carthaginian ships. In the third, the Carthaginian general, Hannibal, is daringly crossing the Alps with his elephants to invade Italy from the North, after having crossed Spain and Southern France. You can see Hannibal, on his white horse, with his red coat blowing in the wind, and his army mounted on African elephants, crossing the white-peaked mountains. Maybe because of this picture, I have always liked Hannibal and read a lot about him. In the fourth picture, depicting the tragic battle of Cannes, we see the Roman soldiers hastily retreating while the Carthaginian elephants charge them with fury, crushing their bodies under their heavy feet or throwing them up in the air with their trunks. The fifth picture shows the battle of Zama, in North Africa, where the African cavalry of Massinissa, allied of Rome, attacks and defeats Hannibal’s army. In the last picture, the Roman army is attacking the city of Carthago to wipe it off the face of the earth. You see Roman soldiers coming on every side, but in the forefront, a Carthaginian woman and her young son, are throwing stones against the overwhelming invading enemies. My eyes still water remembering this picture. I have always liked the underdogs. In spite of being a Roman citizen by birth, that hopelessly brave lady and her child won my heart for Carthago forever.

When I was more or less six, my parents took us and some European friends to visit the ruins of Carthago, close to Tunis. Twenty one centuries ago, when the Romans decided to destroy Carthago completely, they were not joking. Only a few stones half buried in the sand and some half destroyed walls are all that I remember. Palms were growing here and there, and you could see the Mediterranean Sea close by. However, because of the illustrations of the History of Italy, assembled by Isabella, I was fascinated by every little remnant of Carthago, imagined the Roman legionnaires swooping in from everywhere and me being that little Carthaginian boy throwing stones and everything became alive.

Father gave us the love of History and Culture, Mother the means and tools to retain it and absorb it and make it our own.

Today I have just learned that Dino and Marcia called their newborn little girl Isabella! What a wonderful day to continue Isabella Guadagni’s biography. It was 1952. The Arabs in Tunis were becoming restless. Seven years earlier, in 1945, their neighbor Libya, as you remember an Italian colony, had been granted independence by the Allies because of their help in the war against the German and Italian armies. Now Tunis, a French colony, wanted independence too. The leader of the Tunisian Independence Movement, Habib Bourghiba, had been arrested by the French police and put in jail. Some of the Tunisian rebels started to use violence. Tonino was riding on the back open terrace of a trolley bus, when a “Molotov bomb” (a lit gasoline bottle that would explode as soon as it touched something or somebody) flew one inch from his face.

Another day, Pauline took us three children for a walk. I was seven, Bernardo five and Eleonora three. She was sitting in a stroller, Bernardo and I were holding the sides of the stroller, one on either side. Pauline was pushing it. It was a beautiful spring morning, with a sunny and cloudless blue sky. For some reason we were walking towards the Arab Kasbah (Arab part of town), that was not very far from our neighborhood. The Kasbah was the old part of Tunis, surrounded by a wall, with narrow streets and little markets and white washed houses, and donkeys and camels. The French part of town instead, where we lived, was made of wide tree-sided avenues with houses with yards.

At the end of the street in which we were walking there was a door of the Kasbah. Suddenly a group of Arabs, that was getting bigger and bigger every second, started rushing out of the Kasbah door. They were mostly men but also women and children running and throwing stones toward the French quarter and yelling in French and Arabic: ”Free Bourghiba…!Free Bourghiba!”

Pauline saw the danger in which we were so she quickly turned the stroller around and started moving as fast as she could in the opposite direction. However I have always been curious and wanting to be in the middle of the action. Furthermore I wanted to get a closer look at all these Arabs, because in our neighborhood there were very few Arabs, all dressed in a European fashion. Instead these Arabs who were wearing “burnous” and other characteristics Arabian clothing fascinated me. At seven I did not know they were rebels fighting the European for independence, I thought they were just having fun yelling and screaming and throwing stones all over the place. So I let go of the stroller and started running towards the Arabs. Plus I did not know at the time that I was shortsighted and that I needed to get really close to have a good view of things.

“Francois, come back here!” shouted Pauline and ran after me with the stroller and Bernardo running on his little legs. However, getting closer to them I noticed that the Arabs were not playing but had an angry look on their faces and were throwing stones also in my direction. A teenager started running towards me and I did not like the expression on his face. So I turned quickly around and rejoined Pauline and my siblings. We started running as fast as we could. In front of us was the lonely deserted avenue, behind us the Arabs were catching up. A stone hit Pauline on her leg. We arrived at an intersection. Where to go from here? Suddenly we noticed another crowd of Arabs yelling and throwing stones coming from the opposite direction. I remember not being afraid but having fun. I was wondering with amusement where Pauline and we could escape with Arabs coming on all sides.

Suddenly the front door of a house opened and a French lady told us: ”Quick, come here!” We ran inside the door and the lady whispered: ”Go in the basement and be quiet! Do not make any noise…” She opened the basement door and we tiptoed down the stairs. She followed us and locked the basement door behind her. To my great surprise there were at least twenty other people in the basement, most of them standing because there were not enough chairs for everybody, all of them silent as statues.

A few minutes later we heard the crowd of the Arabs reaching the outside of the house where we were hiding. From the basement windows we could see their feet in typical Arabic slippers and sandals running or walking fast on the sidewalk along the house. We heard a loud noise of breaking glass which lasted for a long time. Then the feet became scarce and dispersed and finally disappeared completely and the street was silent again.

The lady waited a few more minutes then she unlocked the basement door. We all went upstairs. The floor was littered with broken glass and stones. There was not one window of the two-story house that was intact. Everybody thanked the lady for her hospitality and went their way. Kindly the lady tried to contact our parents to reassure them but if I remember well the telephone line was broken. On hearing that we were on foot, another lady offered to take us home in her car. So pretty soon we were home again and Mother was really happy to see us because she was wondering why it took us so long to come back from our walk and maybe she had heard about the riots on the radio. We told her all our adventure very excitedly.

At this point Father and Mother must have decided that Tunis was not the best place to raise a family with little children in that specific historical moment. I think Father asked to be transferred and was soon called back to Rome to work in the Department of Foreign Affairs.

We arrived in Rome sometimes in the spring of 1952. While Tonino and Isabella were looking for an apartment to live in Rome, we children were living with Aunt Tecla Guadagni Bartolini Baldelli, and her husband Uncle Franco, and their two sons, Giovambattista, nicknamed Nanni or Giovanni, and Piero, in their castle of Montozzi., about an hour by car from Florence. Now there is the Autostrada del Sole (“Highway of the Sun”), passing by it, so it only takes half an hour. I thought Montozzi was very cozy. There was no electricity or running water upstairs, so every evening our governess would give us a bath downstairs, I think in Aunt Tecla’s bathroom, and then we would go upstairs to our bedroom with lit candles.

Aunt Tecla had bought a whole series of French illustrated books for children to help Nanni and Piero learn French. Piero was born in 1940, and Nanni in 1938, so they were 4 and 6 years older than me. French was at the time the only language that I knew how to read and I had eyed where those French books were kept in one of the living rooms. So the next morning, as I woke up by myself a little after five, as usual, and getting bored staying in bed while waiting for the “adults” to get up and start the day, I slipped out of bed, tiptoed silently down the stairs and entered the living room. It was summer and the sunlight was already flooding the room. I quickly found the French books and, sitting comfortably on a grownup sofa, I started reading them. To my great surprise, I heard a noise of adult footsteps in the nearby dining room. I did not think any adult would get up before seven and I felt guilty because I had not asked anybody permission to get up so early in the morning and roam around a house that was not mine touching things that I was not told I could.

Before I could think of a place to hide or at least put back the French books where they were normally kept, Uncle Franco came smiling broadly into the room. He joyfully said: ”Already up?” and I felt immediately at ease with him. I asked him why he was up so early and he told me he was going fishing. What immediately struck me was that he was wearing shorts. At that time, in Europe, boys wore shorts till they were teenagers, but I had never seen an adult wearing shorts. Tonino was always very elegant and formally dressed and I have never seen him wear shorts in his whole life, even when we were vacationing in the mountains at La Traversa. The only time I saw him wearing shorts was in an old picture book with photographs of him as a colonial officer in Ethiopia. I could not hide my surprise so I asked him: ”Uncle Franco why are you wearing shorts?” He looked at me surprised that I would even need to ask such a question and answered with a smile: ”Because they are more comfortable to go fishing.”

Isabella and Tonino found a small apartment in Rome on top of a an apartment building with a huge terrace, large as the whole building, where as kids we could ride our bikes, roller skate, run, etc. This is another characteristic of Isabella, that she kept her whole life, she wanted her children and later on, her grandchildren, to be healthy. We lived all over the world, but Isabella always rented houses with a big yard, except in Rome where houses with yards are almost inexistent, because she wanted us children to stay outside as much as possible. Every time we were home and it was nice outside she would tell us: ”Go out kids, it is a nice outside!” When I was a child I did not like to play sports, instead I liked to read and draw, two things that are best done inside. But I knew that on having us staying outside when the weather was nice my mother was inflexible. There were no “buts” or “ifs”. And so I would always obey promptly even if sometimes a little grudgingly.

The apartment where we lived in Rome was in Via Tagliamento, next to Via Po’, a long straight street that passed through Piazza Quadrata and ended up near the Roman walls. It was close to via Novara, where I was born. Rome was the only place where we attended a public school. We lived in Rome one year and a half so I did third grade and half of fourth, the only school years that I did in Italian. So as an Italian I have a fourth grade elementary culture. However, at eighteen I was allowed to enroll in the best University of Political Sciences in Italy, the “Cesare Alfieri” of Florence, because I had a French Baccalaureat (“French High School diploma”) which the Italian Government considered equivalent to the Italian High School diploma. I had no problems in school and I quickly caught up to my Italian schoolmates’ level. Bernardo did the same. Eleonora was not going to school yet. She was attending kindergarten. My only problem was the Italian “r”, which is loud and rolling, I had the French “r” soft and whispered and I still do. Sometimes I have a problem teaching Italian words with an “r” in it because I cannot pronounce them correctly.

In Rome we had a maid called Betta. She was a strong, hairy, nice and gentle Sardinian woman from a little mountain town of that island. I think she must have been in her thirties even though her hair was gray. On the day she arrived, Isabella showed her the apartment. There were two bathrooms, one was the masters’ and one was the servants’. When Isabella took her in the masters’ bathroom, Betta looked surprised and whispered in my mother’s ear: ”Madam, why do you have that in here?” indicating the toilet. “Why not?” asked Isabella taken aback. “I thought only us poor people had to do “those things”. I thought upper class and nobles did not have to.” Isabella smiled: ”Yes Betta, we all do”.

Isabella and Tonino were very popular in Rome, so they were often invited out for dinner. We remained home with Betta, who often cooked cream of wheat for dinner. She also walked us to school and picked us up.

In Rome we saw more of our parents, maybe because we had no governess, and the apartment was smaller, and our parents had less “job social obligations”. Tonino had had a very strict upbringing and both of his parents used the whip as a correction tool. So with us he never touched us. Only once, in Rome, was I “physically corrected”. Eleonora was crying because I had punched her in the stomach. When my father heard about it he asked me in the living room. He asked me to stretch out my open hand towards him and he slightly tapped it. It was mostly symbolic because it did not hurt at all. He looked at me straight in my eyes and said with a serious voice:”Remember…never hit a woman!”

When I was a kid, I was very skinny and nervous, I would easily loose my temper. In Tunis a French schoolmate once said:”Quel mauvais caractere il a Francois!”(What a bad temper Francois has!). Sometimes when things were not going my way I would start screaming very loudly non stop. At that point Isabella would quickly slap me on the cheek. One slap was enough…I would immediately stop crying and calm down. I do not think Isabella slapped me more than three times in my whole life. That is why we children were not afraid of our parents, they never hurt us physically or with angry words.

Today I will talk about La Traversa. La Traversa was a house we had in the mountains, on the Apennines, half way between Florence and Bologna, on the “continental divide” we would say in Colorado, i.e. on the highest part of the mountain chain in that area. From Florence it was about 30 miles. The road, called Via Bolognese, because it was going towards Bologna, would start sloping gently North of Florence, among villas and castles and cultivated farmland and then all of a sudden it would start climbing steeply on the mountain, zigzagging between thick forests and steep rocky cliffs, until the Futa Pass, the highest point of the road. Then it entered a large mountain valley, with the town of Firenzuola (Little Florence) visible far down at the bottom of it, with cultivated farmland around it. However, the road followed the mountain tops, crossing through the very small villages of La Traversa, Covigliaio and Pietramala, each one two or three miles apart, and then would gently start going down towards Bologna. On the left of the road were the wooden mountain tops, on the right with a beautiful infinite view was the Firenzuola valley, which seemed to last forever, far below us. Between La Traversa and Covigliao on the left was the highest peak of the region, called Sasso di Castro. It was all rocky cliffs with very few trees, attached on the side of the cliffs or on top of the mountain. “Castrum” meant Roman Army encampment in Latin, and so the name of the mountain meant “Rock (sasso) where the Roman Army was encamped.”

From the top of the mountain, rocky and barren, on the cloudless clear mornings you could see the Tyrrhenian Sea on the West and the Adriatic Sea on the East, i.e. the whole of Italy in its width. A big wooden cross was on top of the mountain. It was carried to the top of the Sasso di Castro and planted there on a Summer Sunday when I was a little child by the Priest of the only church of La Traversa with a long procession of the inhabitants of the whole town including us, up the steep dirt and rocky path, which lasted all morning. On top the Priest blessed it and we all knelt down. Our house was 200 yards from the bottom of the mountain and on summer afternoons we would often take a three hour walk to the top and back.

La Traversa and all the valley of Firenzuola have been very dear to the Guadagni Family for over a century. They always owned two or three villas in it and/or some farmland. All of them or some of them, I am speaking of the Guadagni Family as a whole, would spend part of the summer and fall or all of it in it every year.

It all started with Guadagno Guadagni (1833-1905), our common great-grandfather. Let us remember he was the only Guadagni male of his generation. He had four sisters, one of whom, Aurora, married the Belgian Baron Adrien van der Linden d’Hooghvorst, whose mother, Emilie d’Oultremont van der Linden d’Hooghvorst started an order of nuns after the death of her husband and was beatified by Pope John Paul II on 10/12/1997. Guadagno was a daring and adventurous young gentleman. As a young man he spent many years as a page of the King of Bavaria, in Germany, because there was no military academy in Florence. He was attached to the service of Queen Mary of Bavaria. In 1851 he became artillery lieutenant of the Bavarian Army. In 1854 he fought against the Russians in the Crimean War as a British officer. His grandfather, Sir Francis Lee, was Viceroy of the British Empire of India. His mother was Lady Luisa Lee, a British gentlewoman. In 1859, he joined the Tuscan detachment of the Italian Army to fight against the Austrian in the Italian Second War of Independence. In 1860, he fought as the cavalry officer of Garibaldi in the war against the Bourbons in the Kingdom of Naples, contributing to the victory of Volturno against enemy forces almost double his own. If he had been killed in any of these wars the Guadagni Family would have been extinct forever after eight hundred years of existence.

At the end of the war against the Bourbons, one day, when he was strolling on his horse around the countryside near Naples to find forage for his horses he met a beautiful young English maiden, called Luisa Barlow Hoy. From pictures we have of them we can see that Guadagno was very handsome and charming, with a wild dreaming artistic look in his eyes, and Luisa was enchantingly beautiful with a sweet romantic expression on her face. They immediately fell in love. However Luisa was an orphan and was under the custody of a tutor, her uncle. As she was very wealthy, her uncle did not want her to get married so he could continue to administer and enjoy her wealth. He had told the local priest that Luisa could not get married without his consent because he was her tutor. This is what the priest told Guadagno and Luisa when they went to his church to get married. At this point it seems that Guadagno pointed his gun to the forehead of the priest and said:”Father you marry us or I will have to shoot!” Uncle Vieri told me this last part of the story. The priest decided it was safer to marry them so he did.

It was a romantic and passionate marriage that lasted all their life. Luisa was pregnant seventeen times. She had a few miscarriages but eight healthy children, five boys and three girls, crowned their married life. All the five boys, Guitto, Giacomo, Bernardo, Tommaso (called Bebe, because everybody thought he was going to be Guadagno and Luisa’s last child) and Luigi (called Gigi) got married and had altogether eighteen little Guadagni children, twelve boys and six girls, Tony Gaines being one of the boys and my mother Isabella one of the girls.

Guadagno, Luisa and their children, and nannies and servants, all lived in Masseto, the Guadagni property on the hills close to Florence, which had been in the family for eight centuries. However, Masseto, like Florence, during the summer gets very hot and humid. So Guadagno started to search for a possible mountain home for the summer in the Tuscan Apennines.

After looking for a while Guadagno entered the Firenzuola valley from the mountain top road and fell in love with it immediately. He found what he wanted at the foot of the imposing Sasso di Castro. It was an inn. He bought it and transformed it into a Bavarian chalet similar to the ones he saw in Bavaria when he was a page of Queen Mary.

I will describe it as I remember it. During my description, I will recall the few changes that happened from the time Guadagno bought it around 1870. There was one interesting detail that has not changed from the time it was an inn. In the breakfast room of La Traversa, the floor is covered with small red tiles. However in the middle of the room the floor goes up an inch or two in a small heap and the tiles are disconnected and in disorder, as if there had been a small earthquake. I must have been seven years old when I asked my mother the reason for it. Isabella told me there was a legend about it. When La Traversa was an inn, one day, a talented musician customer came and lodged in it. That evening, after dinner, in the “breakfast room”, the musician took out his violin and started playing beautiful dancing music. At the beginning the other customers listened with pleasure and admiration, then, a couple stood up and started dancing in the middle of the room, soon, other customers followed. Quickly the whole room was full of dancers. Sitting in a corner was a nun, who happened to lodge in the inn that evening, on her way to her convent. She was very fond of music. For a while she hesitated, then, she could not resist any longer and joined the rest of the dancers in the middle of the room. The other dancers looked at her with surprise while she was dancing in her long black garments, her veil flowing all over at every one of her movements. The musician played his music faster and faster and the nun seemed to forget everything and everybody following the tunes of the violin.

The other dancers started to clap their hands and encourage her because she was the best of them all. One by one they left the dancing floor to her and sat down on their chairs admiring her virtuoso. Suddenly, with a loud noise and a dark cloud of smoke, the floor opened in the middle of the room and the devil, with a horrible snarl, jumped out of it and grabbing the nun by the waist carried her underground with him straight to Hell. The floor closed after them but not perfectly. And this is why the floor was like that, concluded Isabella. I asked her why the owners of the inn never repaired it, or any of the Guadagni who successively owned and lived in La Traversa. She told me that the ground underneath the breakfast room was hard and rocky and that it was too hard to work on it.

Coming up from Florence, the last miles before Futa Pass were very steep, full of sharp curves with no cultivated farmlands but only woods and rocky cliffs. The last little town before it was called Montecarelli. It had a horse-changing post with an inn, and in the horse-drawn carriage days, travelers would stop there to change the horses before the last steep climb. Futa Pass itself was a deserted place with only one little lodging house with a restaurant and another house for rent for summer tourists a few yards away. It was almost always lost in the clouds or fog. I have only crossed it between the beginning of June and the first weeks of September. I presume a good part of the rest of the year it was covered with snow and ice.

Immediately after Futa Pass the Via Bolognese started gently descending and patches of farmland appeared between the trees. The sky opened wide, not blocked by rocky cliffs anymore, also because we were on top of the “continental divide”. After a mile and a half we would enter the little town of La Traversa. I think our house used to have a different name but I do not recall it and we have always called it by the name of the town. At the beginning of the village of La Traversa was a big farm on the left. It was the only farm of the town and when we were little we enjoyed visiting its barn with cows and calves and horses. Then a few houses started on both sides of the street. The whole town was only two or three hundred yards long on both sides of the road. Behind it were cultivated fields, mostly wheat, and henhouses. I think every house had a little bit of land of which the inhabitants lived on, and a hen and rabbit house for their meat.

The town had no running water. A well, next to the only “grocery store”, was the only source of drinking water for the town and surrounding area. Every morning we or our maids, would walk to it from the house, with large empty wine flasks and get the water supply for the day. A small convent of nuns with a chapel and a few trees around it was on the left. They had Mass at eight o’ clock on Sunday mornings, and we young folks liked to go there for Mass, in the days when you had to fast for Communion since midnight.

Then, on the right would start a steep downhill dirt and rocky road that took you to the village church. It could fit maybe fifty people. The front pew on the left was reserved for our family (When I talk about “our” house, or “our” family I mean the Guadagni and their relatives). The young parish Priest was called Father Desiderio and, if you remember, his sister Miranda, had been our nanny in Tunis. The priest’s house was just behind the church. Next to it, surrounded by thick woods, started a dirt road that took to the village graveyard, passed next to the back of our property and its wooden gate, crossed the little stream, intersected with another smaller dirt road that took to “the castle”, and rejoined Via Bolognese after a while.

After the intersection with the church road there were only three or four houses left before the end of the town. Then, on the right, was a big wooden gate that led to our house. On the left, till the Sasso di Castro and the town of Covigliaio two miles from there, were only farmland and mostly woods climbing up towards the top of the mountains. Not a single house. The first important mountain, just in front of our house was called Cucuzzolo, and then towering above every thing else was the Sasso di Castro.

From now on when I say “La Traversa” I mean the Guadagni house. I will now describe it. La Traversa was built on two intersecting slopes so each of the four sides was at a different height. On the Southern side of the house, the lowest, were four floors, on the Northern, three. On the Western side, there was the front door, facing the Via Bolognese that ran in front of it, and you had to go down quite a few steps to get into the drawing room, facing the Eastern side. The third flour and the fourth floor were on an even level. The Southern side had two floors under the 3rd and 4th, the bottom one had the kitchen, the ironing room and other servants’ rooms, the second was a mezzanine with the servants’ bathroom and bedrooms and the food supply room. The center of the house was a large drawing room, one and a half floor high. The Northern side of the house had only one floor under the 3rd and 4th, including the “breakfast room”, with the uneven floor, and the stone fireplace living room. The drawing room was ten steps lower than the breakfast and living rooms, and ten steps higher than the kitchen. I hope this was not confusing.

The 3rd and the 4th floors were bedrooms. The 4th floor was added by Luigi Guadagni and his wife Antonietta Revedin, because they thought they needed more space to lodge their seven children. As I mentioned before, the house was eventually bought and transformed in a Bavarian Chalet by Guadagno, who lived there every summer with his wife Luisa and their eight children. He kept one or two carpenters all summer long to do the needed works of painting or carpentry or repairs on the house. During the winter there was always a lot of snow falling on the house and in the summer the Guadagni family made the necessary repairs. The Guadagni children were home schooled, mostly by their father Guadagno. It is interesting to read about it in great-uncle Giacomo unfinished memoirs. I will translate them soon. However sometimes Guadagno would ask his sons to give him and the carpenter a hand repairing a wooden balcony, or putting a new carpet upstairs, or painting a wall, and Giacomo recalls they were more than happy to interrupt their homeworks and help Dad repair the house. The Guadagni brothers, Guitto, Giacomo, Bernardo, Tommaso and Luigi were known as daredevils. They would ride their horses bareback all over the Firenzuola valley or on the road back to Florence. Everybody loved them and admired them.

Originally a wooden balcony circled the whole second floor, like in the Bavarian chalets in the Alps. However it took a lot of time and money to keep and upkeep such a long balcony, so eventually, I think after Guadagno’s death, only small balconies were kept, one per bedroom, not attached to one another any more. When Bernardo Guadagni took over the house, he added a large veranda facing the valley with a big covered balcony on top and a tennis court in the park.

When Guadagno died, La Traversa was given to Luigi, Antonietta and their seven children. Tony Gaines remembered La Traversa and he often talked to me about it with a sparkle in his eyes and nostalgia. La Traversa’s back yard was a five acres park sloping down from the house towards the valley. It was full of big oak trees that the Guadagni had planted. One of them was huge: it was called “il Quercione” (quercia in Italian means “oak tree” and quercione is “big oak tree”) and it was over one hundred years old. Sometime, during its life, the top of it had been struck by lightning, and so instead of growing in height it had grown in width. Its large branches were spreading horizontally forever and then eventually shoot up towards the sky. It was like a whole wooden city logged on its massive trunk. Part of its dirt base had been taken away by spring rains so some gigantic roots were coming out of the soil, like the feet of a colossus. Tony, Zato and their siblings used to climb barefooted on the Quercione to the very top of all of its branches. When we were kids we would see little marks left on the bark of the tree by the young Guadagni feet half a century before and we would be amazed by their daring and audacity on climbing to the hardest spots.

The third floor had altogether seven bedrooms lined on both sides of a long turning wooden narrow hall. One was a one bed bedroom all the others had two and one had three beds. There was no central heating in the house. Every room, including the bedrooms, had a wood stove to warm it up. I lived there only in the summer so I do not remember ever having to light the stoves. However Isabella, who lived there with her parents every year till December, because Bernardo liked to go woodcock shooting, remembers just turning on the stoves of the three bedroom where they slept, and that were close to each other, and that as soon as she walked down the long hall towards the other side of the house she was freezing.

The third floor was connected to the second floor by two staircases, one wooden and narrow on the South side, and one wide and in stone on the North side. The latter connected the bedrooms upstairs with the living room, breakfast room and eventually drawing room downstairs, the former with the servants mezzanine on the second floor and the kitchen and ironing room on the first floor. The fourth floor, added by Luigi, and that included three bedrooms, two of which were very wide and could contain four beds each, was only connected to the rest of the house by the South side wooden staircase.

Once you got to the second floor however the two sides of the house were connected by a long dark hall and a few steps leading up or down in all directions.

This large house, like other old houses, had only one bathroom. There were however also two toilets, both with sink and bidet, one in the mezzanine for the servants, and the other on the second floor, next to the bathroom. The bathroom had a bathtub, on four metal feet, a toilet, a sink and a wood burning water heater. The bathroom was long and mostly empty. In one corner there was a basket full of wood. Each one of us, upon entering the bathroom to take a bath, first of all had to add wood to the wood burning water heater so the fire would not go out and the next person would have hot water for his bath. The heater contained only enough water for one bath, that is why in the morning, when everybody needed to take a bath, it was important to keep the fire in the wood burning water heater going. And the water heater did not allow an abundant bath either. Isabella had taught us not to put more than two inches of water in the tub or else our bath would probably be cold.

The town of La Traversa, as I mentioned before, had no running water. For this reason, Bernardo or Luigi (one of them, I do not remember who), had attached a pipe from the house of La Traversa to a spring up in the Cucuzzolo mountain. This pipe would bring the water to a big water tank, located on the fourth floor and would continue filling it up until a plug would close the pipe when it was full. After the morning baths and for a good part of the day, we could hear the mountain water noisily falling in the half empty tank.

Sometimes some leech would get in the spring water, and then suddenly jump out of the tap in our bathroom water. As children we were terrified and immediately jump out of the tub with loud screams. Quickly an adult would come to our aid and pick up the leech with a paper towel and throw them in the toilet. Nobody thought about emptying the tub to get rid of the leech because obviously hot water was too precious to waste. In spite of our fear that was all part of the fun and excitement of living at La Traversa!

I will now talk about our gate or house keeper. His name was Beppe, I remember him as very very old. However he and his family had been the Guadagni gatekeepers for ever. He was younger than Bernardo Guadagni and he used to go up the Cucuzzolo with him to shoot at woodcocks. He was married with Caterina, with a son called Angiolino, who was Tony Gaines’ age. Angiolino was married with Rosa and they had a daughter, Franca, a few years older than us kids. If you remember, when Guadagno died, Luigi and Antonietta and children inherited La Traversa. Angiolino was the same age group as Tony Gaines and siblings. During the winter, when Luigi Guadagni and family stayed in Florence, they would take Angiolino with them and pay for him to attend the same expensive private schools their children did. So Angiolino got an excellent education. Unhappily during World War II he started drinking and I remember that when he was serving us at the dining room table at La Traversa sometimes his hands were shaking a little.

Beppe’s house was next to the gate of the property. The Via Bolognese would go next to our house on the second floor. The alley from the gate sloped down rather briskly to the first floor level, where the kitchen door of our house was located. There was a large parking space for several cars and farm trucks. A path along the grass would climb up around the back of the house to the veranda and the drawing room.

Beppe’s house had two floors: the top one, next to the gate and via Bolognese was his living quarters. The bottom one was a big barn for the cow, rabbits, hens, piglets, etc., which faced a long dirt path that led to the kitchen door of our house. Next to the barn was a very large garden full of vegetables of every kind and several plants of raspberries.

Next to the kitchen was a large outdoor brick bread oven where Rosa would bake fresh bread every morning.

We did not have a refrigerator at La Traversa. Rosa baked the bread for the day every morning. Beppe would milk the cow, named Bionda, and bring fresh milk to the house every day. Vegetables were picked daily from the garden. The hens gave us fresh eggs every day. Once a week a farm truck, full of delicious assorted fruit, would drive up from Uncle Cosimo’s farm of Casalino. We would keep the fruit in the “provision room” in the mezzanine. The fruit was kept on the floor or on wooden shelves. Sometimes a mouse or a rat was spotted in the room. Uncle Cosimo and other adults would run after the rodent trying to hit it with brooms, and there were fruit flying all over the place and it was a fun sight for us children. We usually lived in big cities abroad and La Traversa’s life was so different and fun and exciting. The meat was the only thing that our maids had to buy at the town’s butcher, except when we had chicken or rabbit.